Fair Use on Trial: What Two AI Decisions Reveal About the Future of AI and Copyright Law

Kadrey v. Meta and Bartz v. Anthropic

In the span of just 48 hours, two federal judges in the Northern District of California handed down rulings that could shape the future of generative AI—and how much it will cost to build. Both decisions were framed as victories for Big Tech. But a closer reading reveals a far more nuanced—and more consequential—story: one of legal roadmap-making, doctrinal disagreement, and the quiet but seismic re-centering of creators’ rights.

In Bartz v. Anthropic, Judge William Alsup (in his 32 page order) found that training AI models on copyrighted books could qualify as fair use, likening it to the centuries-old practice of human learning. One day later, in Kadrey v. Meta, Judge Vince Chhabria (in his 40 page decision) reached the opposite conclusion in tone and substance, scolding Meta’s arguments, lamenting the plaintiffs’ failure to put forth their best legal argument, and setting out the path of a future case that would be more likely to succeed in his courtroom.

Taken together, the two decisions do more than reflect judicial disagreement. They bring to the surface the legal, economic, and philosophical tensions at the heart of the generative AI revolution: Is ingesting copyrighted content an act of innovation or appropriation? Can market harm be speculative, or must it be demonstrable? And when tech moves fast, taking what it wants, must it also stop to pay for what it takes?

This article explores those two cases in tandem; not as isolated rulings, but as legal counterweights that, together, will define how copyright doctrine evolves in the age of artificial intelligence. And for plaintiffs, AI developers, and policymakers alike, the message is clear: the fair use battle is likely far from over. But it’s safe to say that the terrain of the battle has shifted.

Two Cases, Two Courts, Two Visions of Fair Use

On their face, Bartz v. Anthropic and Kadrey v. Meta offer similar procedural postures: authors sued major AI developers for using their books—without permission or compensation—to train large language models (LLMs). In both, the defendants moved for partial summary judgment on the issue of fair use. But from there, the paths diverge sharply.

1. Judicial Philosophy: Educational Analogy vs. Market Integrity

Judge William Alsup, presiding over Bartz, framed the ingestion of copyrighted works for AI training as a form of transformative use. He drew an analogy to the act of teaching schoolchildren to write: we don’t hold schools liable when children write original essays after reading copyrighted texts. So too, he reasoned, should Anthropic be shielded when its AI “learns” from books to generate something new. "Everyone reads texts, too, then writes new texts. They may need to pay for getting their hands on a text in the first instance. But to make anyone pay specifically for the use of a book each time they read it, each time they recall it from memory, each time they later draw upon it when writing new things in new ways would be unthinkable,” Judge Alsup pointed out. (Bartz Order, page 12.)

But Judge Vince Chhabria, writing in Kadrey, wasn’t buying it. He called Alsup’s analogy “inapt,” dangerous even (Kadrey Order, page 3). While human learning is diffuse and idiosyncratic, Chhabria emphasized that LLMs can generate massive volumes of content in moments—some of which may mirror, dilute, or even substitute for the original works. “Using books to teach children to write,” he wrote, “is not remotely like using books to create a product that a single individual could employ to generate countless competing works.” Id.

In essence, Bartz privileges input neutrality—what matters is not what the model ingests, but what it outputs. I agree with this approach, for the most part. Kadrey challenges that logic head-on, highlighting the scale and function of LLMs as inherently different from human inspiration.

2. Market Harm: The Crux of Fair Use

Where the Bartz case revolved around the inputs, and not the outputs of the LLM, Judge Alsup pointed out that if the plaintiffs in that case had shown infringing outputs, plaintiffs would have a viable case for damages. Judge Alsup accepted the idea that AI training, in and of itself, causes no meaningful harm to the market for books. The plaintiffs in Bartz alleged regurgitation and substitution, but Alsup was unmoved, finding that the core use (training) was non-commercial and non-substantive in nature. (Bartz Order page 12.)

Judge Chhabria, by contrast, identified market harm as the determinative issue, and faulted the plaintiffs for failing to address it. He did not rule that Meta’s use was lawful. Rather, he lamented that the plaintiffs “failed to develop a record in support of the right [arguments],” (Kadrey Order, page 5). especially around indirect substitution—where AI-generated works don’t copy verbatim, but compete in the same genre, serve the same purpose, and thereby displace original market demand. He even outlined the precise argument that could have led him to rule the other way, essentially scripting a successful future complaint.

This framing may turn out to be more influential than the ruling itself. Kadrey suggests that when AI developers use copyrighted material to train models that flood the market with functionally competitive outputs—even if not identical—that harm is cognizable and potentially actionable under copyright law. The future will tell if other judges and courtrooms agree.

3. A Roadmap for Plaintiffs—and a Warning to Developers

Both judges acknowledged the unprecedented nature of these disputes. But where Bartz defers to technological progress and lack of substantive, demonstrable harm, Kadrey marks out a pathway from appropriation to compensation.

Chhabria’s opinion reads like a judicial “how-to” for creative plaintiffs: document market dilution, show competition at the functional level, and trace how AI-generated outputs crowd out traditional revenue streams. If that roadmap is followed, he makes clear, courts may be prepared to find infringement even without direct copying or regurgitation. Although sound in theory, that roadmap could be a difficult one to follow in practice. With such a diffuse use of LLMs to create competing works, it’s a broad assumption that plaintiffs will be able to show market dilution and harm that can be directly imputed to the defendant-LLM creators. This difficult task will be compounded by the fact that many authors will create content based on a combination of LLM output and their own creativity. And it raises at least as many questions as it answers. What specific evidence would actually satisfy Chhabria's roadmap? How would plaintiffs isolate AI-caused harm from other market factors?

Meanwhile, AI developers can’t claim full victory in either case. In Bartz, Anthropic still faces liability for storing entire pirated books—an act the court found plainly outside the scope of fair use. And in Kadrey, Meta’s win is an empty victory: it avoids liability only because the plaintiffs’ legal strategy fell short.

Long-Term Legal Implications and the Emerging AI Licensing Economy

If these two cases demonstrate anything, it’s that the fair use doctrine—which has often been both the scapegoat and workhorse of American copyright law—is being pushed to its conceptual limits in the age of generative AI. After these two decisions, we see the emergence of two separate camps: what counts as "transformative," what kinds of market harm are legally cognizable, and what obligations developers owe to the creators whose work forms the basis of their models.

These decisions set in motion three long-term legal and policy consequences:

1. A Tipping Point for “Implied Consent” Narratives

For years, developers of LLMs seemed to work on the assumption that scraping publicly available data—books, news articles, forum posts—was simply “how the internet works.” That rationale is quickly eroding. Kadrey explicitly rejects the notion that innovation justifies unlicensed use. And Bartz limits fair use protection to training contexts only, not data storage. Both courts, in different ways, are signaling that something amounting to implied consent is not a sustainable legal foundation for AI training.

2. Rise of the AI Licensing Market

The days of unlicensed scraping are numbered, if not over. Judge Chhabria’s opinion in Kadrey essentially calls for a functioning content licensing regime. He ridiculed Meta’s claim that requiring licenses would halt innovation: “This is nonsense,” he wrote, referring to the large sums of money LLM developers hope to someday gain from the behemoths they have created. (Kadrey Order, page 38.) The implication is clear; tech companies can and must pay for the works they consume. The real question is, “how much?” We are now likely to see a sharp rise in collective rights organizations, licensing exchanges, and contractual frameworks designed to monetize creative input for LLM development.

3. Legislative Interest Will Accelerate

Congress is watching. At least I hope it is. With courts diverging, legislative clarity may soon follow, whether through amendments to the Copyright Act, the creation of AI-specific rights, or guidance from the Copyright Office. These two decisions add urgency to those efforts and may shape model AI legislation aimed at striking a balance between creator rights and technological progress.

How These Cases Shape the Stakes in The New York Times v. OpenAI

The most closely watched case in this area is The New York Times v. OpenAI, which centers on the unauthorized use of Times content—news articles, analysis, and headlines—in the training of ChatGPT and other OpenAI models. In some crucial ways, that case is a horse of a different color. However, both Kadrey and Bartz can offer previews of how that case might unfold. It may also guide the strategies of the New York Times legal team.

1. If Judge Chhabria Heard the Times Case…

If Kadrey's reasoning is applied, the Times would have a strong claim. Judge Chhabria explicitly acknowledged that AI outputs that compete in the same market as the original—even without word-for-word copying—may constitute fair use violations. News media is precisely such a market. The Times is not alleging mere regurgitation, but something far worse. That ChatGPT substitutes for its product, reducing traffic, engagement, and subscription revenue.

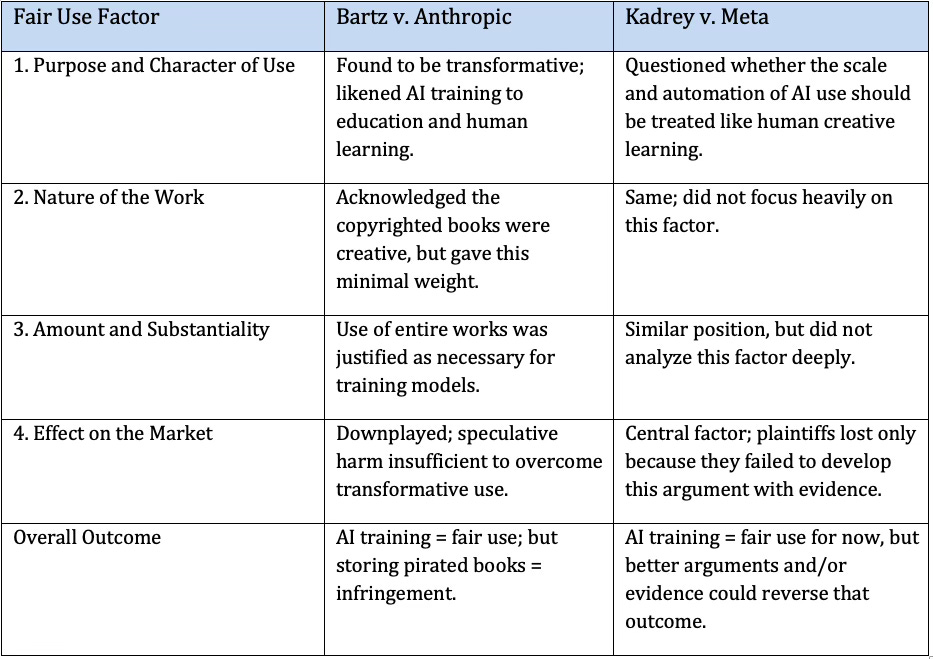

Chhabria made it clear that courts should scrutinize whether generative models dilute or displace commercial markets. In that light, The New York Times has arguably presented the exact arguments that were missing in Kadrey. If their evidence supports it, they may well win on the fourth factor in the copyright analysis (see chart below).

2. Contrast with Bartz: Risks of Overgeneralization

By contrast, if a court adopts Judge Alsup’s reasoning in Bartz, OpenAI may be more likely to prevail. Alsup expressed skepticism toward speculative claims of harm and gave wide berth to technological transformation.

But even Bartz doesn’t offer OpenAI a complete shield: like Anthropic, OpenAI has reportedly retained large quantities of copyrighted material in a usable form, potentially exposing it to claims outside the fair use framework. Judge Alsup explicitly rejected this as “fair use.” More importantly, it is difficult to imagine that Judge Alsup would extend his analogy of a child being taught to encompass the kind of large-scale misappropriation of copyrighted material and commercial exploitation The New York Times alleges in its case. He stated that “if the outputs seen by users had been infringing, [Plaintiffs] would have a different case.” (Bartz Order, page 12.)

3. Strategic Takeaway

The Times case may become the first major copyright trial to fully develop the market substitution theory that Kadrey left undeveloped and Bartz did not address. That makes it a bellwether. And both recent decisions—despite their slightly differing facts and different conclusions—suggest that The New York Times may have built its case on the most durable legal foundation available.

Fair Use Factor Analysis — Bartz v. Anthropic vs. Kadrey v. Meta

Where Doctrine Meets Strategy

The judicial opinions in Kadrey and Bartz add doctrinal weight to the structural analysis I offered in my November 14, 2023 article on AI copyright liability. That article examined who, under U.S. law, is likely to bear responsibility for the ingestion and use of copyrighted materials in AI—from users and service providers to model creators and platform operators.

What Kadrey underscores is how fragile a defendant’s fair use shield becomes when plaintiffs develop the right arguments. Judge Chhabria’s opinion illustrates how market harm—a theme central to both my earlier article and the Copyright Act’s statutory factors—can shift a case dramatically if substantiated. Conversely, Bartz shows the continuing influence of Authors Guild v. Google, a case I analyzed in the context of OpenAI and other LLM developers, is still being felt.

In short, while my prior article framed copyright liability as a question of systems, architecture, and use patterns, Kadrey and Bartz show that individual litigation outcomes may turn on strategic choices. The intersection of both views is critical: fair use will not protect AI developers by default—it must be earned through evidence, design, and respect for economic impact.

As courts continue to explore these questions, it is becoming increasingly clear that doctrinal arguments and platform policies must converge. The decisions in these two cases seem to herald the beginning of the end of the era of legally untethered innovation. The lesson for AI stakeholders is that they can no longer rely on the free gathering of material on the internet. They would do well to align product strategy accordingly.

Beyond Fair Use: The Practical and Geopolitical Stakes of AI Copyright Disputes

In my earlier article on AI copyright liability, I argued that large language model creators like OpenAI are, in many cases, making acceptable use of copyrighted information under current law. That’s particularly true when guardrails prevent regurgitation and outputs are clearly transformative. But Kadrey introduces a different kind of problem: according to the plaintiffs, Meta intentionally scooped up copyrighted materials knowing they were protected—and did so at scale, without permission. That act alone—the knowing, unauthorized acquisition and retention of copyrighted works—is the real wrong. It violates the basic premise of copyright ownership: that the right to control reproduction belongs to the creator.

This is not a question of how much market dilution might result downstream. Judge Chhabria seemed preoccupied with whether AI-generated content could eventually compete with the original works. But that misses the mark. Thousands of authors could write Stephen King-style novels without infringing his copyrights. Similarity, even competition, is not and cannot be the standard. What matters is that Meta (allegedly) deliberately took entire works it had no right to access. To borrow Judge Alsup’s analogy, we wouldn’t excuse a parent or teacher who steals copies of books to teach a child how to read and write. That isn’t about learning, teaching, or inspiration. It’s about misappropriation.

While Kadrey and Bartz deepen the legal framework for analyzing fair use, they seem stuck there, while the cases they preside over expose a far more fundamental issue—one that doctrine alone struggles to capture. As China’s DeepSeek model demonstrates, global AI development will not slow down to observe U.S. copyright laws. Early DeepSeek output admitted the model was heavily trained on ChatGPT 3.5.

Imagine now, for a moment, if American developers are forced to halt training while foreign competitors continue to scrape and scale unchecked. We risk ceding technological leadership not to fair competitors, but to unfair competitors. To actors unconstrained by law. Limiting access to high-quality training data without offering a viable legal pathway—such as reasonable licensing—is a recipe for global imbalance. Yes, copyright holders are entitled to compensation. But not through expansive theories of market harm. The better remedy is simple: developers should pay for what they took at the moment they took it. Not because their users might compete in the future—but because they never had the right to take it in the first place. This path allows for compensation, without crippling imbalance.

Conclusion: From Legal Theory to Market Reality

The twin rulings in Bartz and Kadrey mark more than doctrinal disagreement—they signal the end of AI's legal honeymoon. For three years, the industry operated on the assumption that fair use would provide blanket protection for training on copyrighted content. That assumption is now dead.

What emerges instead is a more complex landscape where legal outcomes depend not on broad principles, but on specific evidence, strategic choices, and judicial philosophy. Bartz shows that well-prepared defendants can still prevail when plaintiffs fail to make compelling arguments. Kadrey demonstrates that even sympathetic judges will craft roadmaps for future plaintiffs when current ones fall short.

But the real lesson transcends these individual cases. Both courts recognize that AI represents a structural shift in how content is consumed, processed, and monetized. The question is no longer whether this shift is innovative—it plainly is. The question is whether innovation alone justifies taking copyrighted works without permission or compensation.

Here, the law is converging on a clear answer: it does not. Judge Chhabria's rejection of the “innovation defense” and Judge Alsup's limitation of fair use to training (not storage) both point toward the same conclusion. The era of ‘technological exceptionalism’ in copyright law is ending.

What comes next will be determined not in courtrooms, but in licensing negotiations, congressional hearings, and corporate boardrooms. The companies that thrive will be those that recognize this shift early and build sustainable relationships with content creators. The ones that cling to “scrape now, ask forgiveness later” will find themselves fighting an increasingly expensive rearguard action.

The stakes extend far beyond individual companies or cases. As China's DeepSeek demonstrates, AI development is now a global competition with national security implications. The United States cannot afford to handicap its own developers with unnecessarily restrictive copyright interpretations. But neither can it ignore the legitimate rights of creators whose work fuels AI advancement.

The solution lies not in choosing between innovation and creator rights, but in building systems that honor both. That means reasonable licensing frameworks, clear legal standards, and recognition that compensation for use is not the enemy of technological progress—it's the foundation of sustainable innovation.

The battle lines drawn in Bartz and Kadrey will shape this new landscape. But the war is not over. Its outcome will be determined by whether stakeholders can move beyond litigation toward collaboration. At least two courts have spoken: the free ride is over. Now, (we can hope) the real work begins.

© 2025 Amy Swaner. All Rights Reserved. May use with attribution and link to article.